How Does Matrix Work: Part 1

Reading time: 20 mins.Understanding Conventions: A Cautionary Note

It might come as a surprise that the information presented here may not align perfectly with what you've encountered in other resources, whether books or online materials. While the core information remains consistent, you might notice variations in the order or sign of matrix coefficients. This discrepancy arises from the different conventions adopted by various authors or software. We encourage you to focus on the logic and principles outlined in this lesson, setting aside discrepancies with other sources for now. The next chapter will delve deeper into how these varying conventions influence both the theoretical presentation and practical implementation of matrices in programming.

By the end of this two-part series on how matrices work, we will provide a clear and definitive summary of the various conventions you may encounter in textbooks, resources, or source code. We'll highlight common sources of confusion, not only from how mathematical equations involving matrices are written on paper but also from their actual implementation in programming. Specifically, we’ll explore the differences between row-major and column-major order, the effects of pre- and post-multiplication, and how matrices relate to other topics, such as right- versus left-hand coordinate systems, which we’ve already covered in the Coordinate Systems chapter.

Don’t worry if you’re unfamiliar with these concepts at the start of this chapter (although you should already know about left- and right-hand coordinate systems if you’ve followed this lesson from the beginning). We will explain everything as we go.

Point-Matrix Multiplication Explored

This lesson aims to synthesize our understanding of points, vectors, matrices, and coordinate systems, paving the way for a comprehensive grasp of how matrices function. Building on the previous chapter's discussion on matrix compatibility for multiplication—specifically, that matrices of sizes \(m \times p\) and \(p \times n\) can be multiplied—we highlighted that in computer graphics, we predominantly work with 4x4 matrices.

Considering that a point or vector can be represented as a sequence of three numbers, they can also be conceptualized as 1x3 matrices. Here’s an illustration of a point expressed in matrix form:

$$P = [x y z].$$By representing points and vectors as [1x3] matrices, we unlock the possibility of matrix multiplication. Keeping in mind that a \(m \times p\) matrix can be multiplied by a \(p \times n\) matrix to result in a \(m \times n\) matrix, if we treat the first matrix as a point (thus, m = 1 and p = 3), it follows that the second matrix must take the form 3 x n, where n is any number greater than 1. Consequently, a [1x3] matrix can be multiplied by matrices of various forms, such as [3x1], [3x2], [3x3], [3x4], etc. Consider the multiplication of a [1x3] and a [3x4] matrix as an example:

$$ \begin{bmatrix}x & y & z\end{bmatrix} * \begin{bmatrix} c_{00}&c_{01}&{c_{02}}&c_{03}\\ c_{10}&c_{11}&{c_{12}}&c_{13}\\ c_{20}&c_{21}&{c_{22}}&c_{23}\\ \end{bmatrix} $$To fully understand the implications, we need to keep two key points in mind. First, multiplying a point by a matrix transforms that point to a new location, meaning the result must also be a point. Second, using matrices for point transformation requires that the result of such multiplication is another point, ideally represented as a 1x3 matrix. Therefore, for the outcome to be a point, the multiplying matrix must be a 3x3 matrix. The product of a 1x3 matrix and a 3x3 matrix, as expected, results in a 1x3 matrix—a transformed point. Here's an example of how such a multiplication would look:

$$ \begin{bmatrix}x & y & z\end{bmatrix} * \begin{bmatrix} c_{00}&c_{01}&{c_{02}}\\ c_{10}&c_{11}&{c_{12}}\\ c_{20}&c_{21}&{c_{22}}\\ \end{bmatrix} $$In computer graphics, while 4x4 matrices are often the standard, there are instances where we initially work with 3x3 matrices. The reasons why 4x4 matrices are more common will be explained later, but for now, let's use 3x3 matrices as a starting point. As we conclude this section of the chapter, we’ll demonstrate through pseudocode how to multiply a point \(P\) (or a vector represented in matrix form) by a 3x3 matrix to yield a transformed point \(P_T\). If you need to review the basics of matrix multiplication, please refer to the previous chapter.

The process involves multiplying each element of a row in the first matrix by the corresponding element of a column in the second matrix (we assume that vectors and matrices are arranged in a row-major fashion for this example, for those familiar with these concepts. For those who aren’t, don’t worry; these will be explained shortly), then summing these products to compute each element of the resultant matrix. The pseudocode below illustrates this process, and we’ll cover the 4x4 matrix case later:

// For the x-component, combine row 1 elements with column 1 elements Ptransformed.x = P.x * c00 + P.y * c10 + P.z * c20 // For the y-component, combine row 1 elements with column 2 elements Ptransformed.y = P.x * c01 + P.y * c11 + P.z * c21 // For the z-component, combine row 1 elements with column 3 elements Ptransformed.z = P.x * c02 + P.y * c12 + P.z * c22

Understanding the Identity Matrix

The identity matrix, also known as the unit matrix, is a special type of square matrix (square meaning the number of columns and rows are the same). Its off-diagonal elements are all zeros, while the diagonal elements are all ones:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} \color{red}{1} & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \color{red}{1} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \color{red}{1} \end{bmatrix} $$Multiplying a point \(P\) by the identity matrix yields \(P\) itself. This property becomes evident when we integrate the identity matrix coefficients into our point-matrix multiplication pseudocode, illustrating the identity matrix's role in preserving the original point:

// Multiplying P by the identity matrix results in P Ptransformed.x = P.x * 1 + P.y * 0 + P.z * 0 = P.x Ptransformed.y = P.x * 0 + P.y * 1 + P.z * 0 = P.y Ptransformed.z = P.x * 0 + P.y * 0 + P.z * 1 = P.z

Exploring the Scaling Matrix

When examining the process of point-matrix multiplication, it becomes clear that the coordinates of point \(P\) are individually multiplied by specific coefficients along the matrix's diagonal: \(R_{00}\) for the x-coordinate, \(R_{11}\) for the y-coordinate, and \(R_{22}\) for the z-coordinate. Setting these diagonal coefficients to 1, with all other matrix elements set to 0, results in the identity matrix, which leaves \(P\) unchanged. However, altering these diagonal values to something other than 1 scales the point's coordinates up or down, depending on whether the values are greater or smaller than 1.

This ties back to our discussion on coordinate systems, where we noted that scaling a point's coordinates is achieved by multiplying them by scalar values. The only difference here is that the scale can be applied independently to each coordinate of the point, with different values for each axis. Consequently, the scaling matrix is expressed as:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} \color{red}{S_X} & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \color{red}{S_Y} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \color{red}{S_Z} \end{bmatrix} $$Here, \(S_X\), \(S_Y\), and \(S_Z\) represent the scaling factors for each respective axis.

// Applying the scaling matrix to P Ptransformed.x = P.x * Sx + P.y * 0 + P.z * 0 = P.x * Sx Ptransformed.y = P.x * 0 + P.y * Sy + P.z * 0 = P.y * Sy Ptransformed.z = P.x * 0 + P.y * 0 + P.z * Sz = P.z * Sz

For instance, consider a point \(P\) with the coordinates (1, 2, 3). Applying a scaling matrix with \(Sx = 1\), \(Sy = 2\), and \(Sz = 3\) transforms \(P\) into a new point with coordinates (1, 4, 9), effectively scaling each coordinate by the specified factors.

It's also worth noting that using negative values for any of the scaling coefficients will invert the corresponding coordinate across that axis, akin to reflecting the point across the axis. This feature allows for mirror transformations in addition to scaling.

Understanding the Rotation Matrix

This section delves into constructing a matrix that rotates a point or vector around an axis within the Cartesian coordinate system, utilizing trigonometric functions for the operation.

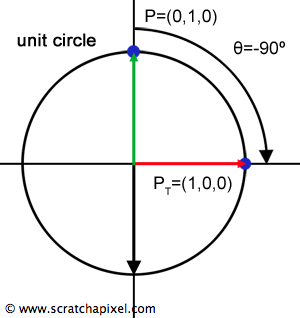

Consider a point \(P\) in a three-dimensional space, positioned at (1, 0, 0). Temporarily disregarding the z-axis and focusing on the xy plane, our goal is to rotate \(P\) to a new position \(P_T\) with coordinates (0, 1, 0). This rotation can be visualized in Figure 1, where \(P\) is rotated 90 degrees counterclockwise around the z-axis to reach \(P_T\). Suppose we have a rotation matrix \(R\). Multiplying \(P\) by \(R\) results in the transformation of \(P\) to \(P_T\). To understand this transformation through matrix multiplication, let's break down the calculation for each coordinate of the transformed point:

$$ \begin{array}{l} P_T.x = P.x * R_{00} + P.y * R_{10} + P.z * R_{20}\\ P_T.y = P.x * R_{01} + P.y * R_{11} + P.z * R_{21}\\ P_T.z = P.x * R_{02} + P.y * R_{12} + P.z * R_{22}\\ \end{array} $$

For our purposes, \(P_T.z\) is of lesser concern since its value remains unchanged under this rotation. Our focus will be on \(P_T.x\) and \(P_T.y\), which represent the x and y coordinates of \(P_T\), respectively. Observing the transition from \(P\) to \(P_T\), the x-coordinate changes from 1 to 0, indicating that \(R_{00}\) must be 0. Given that both \(P.y\) and \(P.z\) are zero, the exact values of \(R_{10}\) and \(R_{20}\) are momentarily irrelevant. As \(P\) transitions to \(P_T\), the y-coordinate increases from 0 to 1. Since \(P.x\) is 1 and its other coordinates are zero, this implies \(R_{01}\) must be 1.

In summary, we have deduced that \(R_{00} = 0\) and \(R_{01} = 1\). Let's write this down and compare what \(R\) looks like relative to the identity matrix:

$$ R_z= \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} $$At this point, don’t worry about the specific values of the coefficients—clarification will follow. The key takeaway is that applying this rotation matrix to \(P = (1, 0, 0)\) results in \(P_T = (0, 1, 0)\), demonstrating the matrix’s role in rotating a point or vector when the point is multiplied by this matrix. Continuing from the discussion on the rotation matrix, when applying the matrix \(R\) to transform \(P\) into \(P_T\), the operation simplifies to:

$$ \begin{array}{l} P_T.x = P.x * 0 + P.y * 1 + P.z * 0 = 0\\ P_T.y = P.x * 1 + P.y * 0 + P.z * 0 = 1\\ P_T.z = P.x * 0 + P.y * 0 + P.z * 1 = 0\\ \end{array} $$

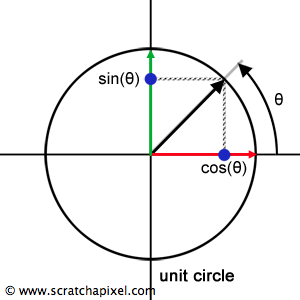

Knowledge of trigonometric functions will now turn out to be handy. As you know, for a point on the unit circle, its x and y coordinates correlate with the cosine and sine of the angle \(\theta\), respectively, as illustrated in Figure 3:

$$ \begin{array}{l} x = \cos(\theta) = 0\\ y = \sin(\theta) = 1\\ \text{given } {\theta = {\pi \over 2}}\\ \end{array} $$At \(\theta\) = 0, we find x = 1 and y = 0. At \(\theta\) = 90 degrees (or \(\pi \over 2\)), x becomes 0 and y turns to 1. Interestingly, these values correspond to \(R_{00}\)/\(R_{11}\) and \(R_{01}\)/\(R_{10}\), allowing us to redefine the rotation matrix \(R\) for a \(\theta\) of 90 degrees (\(\pi \over 2\)) as:

$$R_z(\theta)= \begin{bmatrix} \cos(\theta) & \sin(\theta) & 0 \\ \sin(\theta) & \cos(\theta) & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \text{ with } {\theta = {\pi \over 2}} $$Applying a 45-degree rotation (\(\pi \over 4\)) using \(R\) to \(P\), \(P_T\) achieves coordinates (0.7071, 0.7071), confirming the correctness of this approach (Figure 2). Hence, the rotation matrix for the z-axis becomes:

$$ R_z(\theta)= \begin{bmatrix} \cos(\theta) & \sin(\theta) & 0 \\ \sin(\theta) & \cos(\theta) & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} $$However, if we use this matrix to perform a rotation of -90 degrees (a 90-degree rotation, but clockwise this time) (Figure 4), does this matrix transform \(P = (0, 1, 0)\) to \(P_T = (1, 0, 0)\)? Let’s check:

$$ R_z= \begin{bmatrix} \cos(-{\pi \over 2}) & \sin(-{\pi \over 2}) & 0 \\ \sin(-{\pi \over 2}) & \cos(-{\pi \over 2}) & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix}= \begin{bmatrix} 0 & -1 & 0 \\ -1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} $$ $$ \begin{array}{lll} P_T.x = &0 * R_{00} &+& 1 * R_{10} &+& P.z * R_{20} &= \\ &0*0 &+& 1*-1 &+& 0*0&=-1\\ P_T.y = &0 * R_{01} &+& 1 * R_{11} &+& P.z * R_{21} &= \\ &0*-1 &+& 1*0 &+& 0*0&= 0\\ P_T.z = &0 * R_{02} &+& 1 * R_{12} &+& P.z * R_{22} &= \\ &0*0 &+& 1*0 &+& 0*1&= 0\\ \end{array} $$The direct application yields \((-1, 0, 0)\) instead of \((1, 0, 0)\). Looks like this matrix doesn’t work. Let’s correct it. The proper rotation matrix for a clockwise rotation should be:

$$ R_z= \begin{bmatrix} \cos(-{\pi \over 2}) & \sin(-{\pi \over 2}) & 0 \\ -\sin(-{\pi \over 2}) & \cos(-{\pi \over 2}) & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix}= \begin{bmatrix} 0 & -1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} $$ $$ \begin{array}{lll} P_T.x = &0 * R_{00} &+& 1 * R_{10} &+& P.z * R_{20} &= \\ &0*0 &+& 1*1 &+& 0*0&=1\\ P_T.y = &0 * R_{01} &+& 1 * R_{11} &+& P.z * R_{21} &= \\ &0*-1 &+& 1*0 &+& 0*0&= 0\\ P_T.z = &0 * R_{02} &+& 1 * R_{12} &+& P.z * R_{22} &= \\ &0*0 &+& 1*0 &+& 0*1&= 0\\ \end{array} $$This time, it yields the correct transformed coordinates of \(P_T = (1, 0, 0)\). This matrix accurately rotates points around the z-axis, whether we rotate the object counterclockwise (using a positive rotation angle) or clockwise (using a negative rotation angle), without altering the z-coordinate, of course.

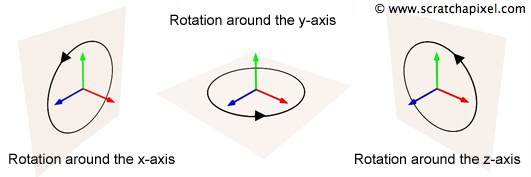

The matrices for rotations around the x and y axes can be derived similarly, with \(R_x\) affecting rotations in the yz plane and \(R_y\) in the xz plane. Here are the matrices for rotations around the x and y axes (with \(R_z\) for completness):

$$ R_x(\theta)= \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & \cos(\theta) & \sin(\theta)\\ 0 & -\sin(\theta) & \cos(\theta)\\ \end{bmatrix} $$ $$ R_y(\theta)= \begin{bmatrix} \cos(\theta) & 0 & -\sin(\theta)\\ 0 & 1 & 0\\ \sin(\theta) & 0 & \cos(\theta)\\ \end{bmatrix} $$ $$ R_z(\theta)= \begin{bmatrix} \cos(\theta) & \sin(\theta) & 0\\ -\sin(\theta) & \cos(\theta) & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 1\\ \end{bmatrix} $$To calculate the transformed point's coordinates, you multiply the point's coordinates by the coefficients in each column of these matrices, ensuring a consistent approach to point transformation across different axes of rotation.

If you've been comparing the rotation matrices provided here with those on Wikipedia's page about rotation matrices and noticed discrepancies, you're not alone. The matrices listed on Wikipedia appear as follows:

$$ \begin{alignat}{1} R_x(\theta) &= \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \cos \theta & -\sin \theta \\[3pt] 0 & \sin \theta & \cos \theta \\[3pt] \end{bmatrix} \\[6pt] R_y(\theta) &= \begin{bmatrix} \cos \theta & 0 & \sin \theta \\[3pt] 0 & 1 & 0 \\[3pt] -\sin \theta & 0 & \cos \theta \\ \end{bmatrix} \\[6pt] R_z(\theta) &= \begin{bmatrix} \cos \theta & -\sin \theta & 0 \\[3pt] \sin \theta & \cos \theta & 0 \\[3pt] 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \end{alignat} $$Indeed, these appear quite different from the ones we've discussed. However, this discrepancy underscores the critical importance of understanding the conventions underpinning these matrices. To accurately interpret a matrix, you need to know:

-

Whether the coordinate system is left-handed or right-handed.

-

Whether the matrices are used in column-major or row-major order.

The Wikipedia article specifies that the matrices are based on a right-hand coordinate system (similar to our usage on Scratchapixel) but employs the column-major convention. We use the row-major order convention. This difference means that to align Wikipedia's matrices with ours, one must transpose them. A matrix transpose—detailed in our Matrix Operations chapter—leaves diagonal coefficients unchanged while flipping the others across the diagonal. For example, a coefficient at position m[0][1] moves to m[1][0] after transposition. Applying this transposition to Wikipedia's matrices yields matrices identical to ours:

This highlights the importance of understanding the conventions used, particularly regarding coordinate systems (left-handed or right-handed) and matrix order (row-major or column-major). The choice of convention is flexible, as long as it is clearly communicated to others who may use your code. On Scratchapixel, we consistently use right-handed coordinate systems and row-major matrices. Why do we use these conventions? Because throughout most of our professional careers, we have worked with software like Maya and PRMAN, both of which use a right-handed coordinate system and row-major matrix order.

However, other tools, such as Blender, Unreal Engine, or graphics APIs like OpenGL and DirectX, may use different conventions. Fortunately, modern APIs generally allow you to configure these settings to your preferences, which wasn’t the case until a few years ago.

Now, some might argue that the system they grew up using should be the standard for everyone. I understand that argument, but in the interest of helping future generations of programmers and graphics artists, I believe the most logical convention is to use a right-handed coordinate system and row-major matrices. Why are row-major matrices a better choice, in my opinion? Because they match the way coefficients are laid out in memory—a topic I will discuss later in this lesson. So please, do use these conventions in your projects.

Navigating the realm of computer graphics programming, one quickly realizes that the concepts of "right" and "wrong" are often not as clear-cut as they seem. If you’re feeling bewildered by encountering different sets of equations in various resources, it’s not necessarily because they are wrong, but because the authors may use different conventions, leading to flipped signs on certain terms. So, before assuming an equation is incorrect, first check which conventions are being used.

While it can be frustrating to juggle different sets of equations that encode the same principles, this is, unfortunately, a natural part of the learning curve in computer graphics. You may start with a book that presents one methodology, only to encounter different approaches elsewhere, such as on Scratchapixel. As you progress in your career, you'll likely encounter these variations almost daily. Rather than seeing them as obstacles, view them as opportunities to deepen your understanding and enhance your flexibility in navigating the sometimes confusing landscape of computer graphics and interactive programming.

Note that one of the main reasons I started Scratchapixel was precisely to help artists and computer graphics programmers become aware of these conventions and educate them on these topics. Throughout my career, I’ve seen people repeatedly asking the same questions, and in most cases, their issues were due to confusion around coordinate system handedness or matrix layout. Had these individuals been provided with the right and clear resources to learn about these questions, they could have saved themselves a lot of trouble and wasted time. I wrote this content with that goal in mind, and I hope it achieves that objective.

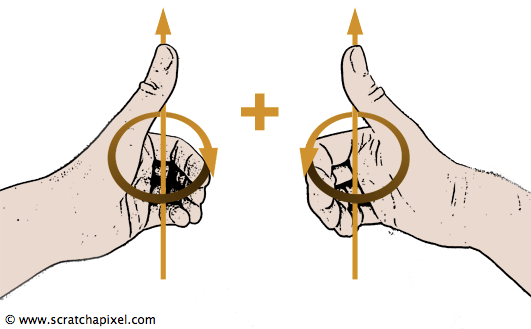

Remember, you can use the mnemonic technique mentioned earlier in the lesson to help you easily determine the direction of rotation for positive angles, whether you're using a right-hand or left-hand coordinate system. Curling your fingers around the axis of rotation, as shown in Figure 6, will indicate the direction of positive rotations:

-

Right-hand system: Counterclockwise.

-

Left-hand system: Clockwise.

Synthesizing Rotation Matrices

From the insights gained in the preceding chapter, we understand that multiplying matrices effectively combines their transformation effects. With the knowledge of how to perform rotations around each cardinal axis, we are now equipped to create more intricate rotational dynamics by combining \(R_x\), \(R_y\), and \(R_z\) matrices. For instance, if the goal is to first rotate a point around the x-axis, followed by the y-axis, this can be achieved by constructing two matrices, \(R_x\) and \(R_y\), and merging them through matrix multiplication (\(R_x \times R_y\)) to create a composite \(R_{XY}\) matrix that incorporates both rotations.

$$R_{XY} = R_X * R_Y$$It's crucial to note that the sequence of rotations significantly impacts the outcome. Rotating a point first around the x-axis and then around the y-axis typically produces a different result than performing these rotations in reverse order. This is why, in mathematical terms, we say that matrix multiplication is not commutative. In general, for two matrices \( A \) and \( B \), the product \( A \times B \) is not the same as \( B \times A \). In other words:

$$A \times B \neq B \times A$$This is a key property of matrix multiplication, and it's important to remember when dealing with transformations in computer graphics. The order in which matrices are multiplied affects the outcome. This principle of rotation order is a fundamental aspect in many 3D modeling and animation software like Maya, 3DSMax, Softimage, and Houdini, where users can specify the rotation sequence, such as xyz, or zyx among other configurations.

Introducing the Translation Matrix

To facilitate point translations using point-matrix multiplication, we need to use 4x4 matrices instead of 3x3 matrices, which can only encode rotation (and scaling). Since our current discussion is limited to 3x3 matrices, the specifics of using matrices for translations will be explained in the Transforming Points and Vectors chapter.

Rotations Around an Arbitrary Axis

It is possible to create a function that rotates a point or vector around any (arbitrary) axis. This topic will be covered in future updates to this lesson series, after a deeper look at foundational concepts.