Points, Vectors and Normals

Reading time: 15 mins.Geometry is a branch of mathematics concerned with questions of shape, size, the relative position of figures, and the properties of space.

Why This Lesson Matters and What You'll Learn

This lesson is comprehensive and may present a challenge for many, especially if you're new to computer graphics. However, there's a silver lining, and here's why diving into this lesson is worthwhile:

1) Starting Point in Computer Graphics: Unlike many textbooks that recommend beginning with the theoretical aspects of geometry, we suggest a different route. Start with the "3D Rendering for Beginners" section to dip your toes into the world of computer graphics. This approach allows you to engage with the material more interactively and see the application of these theories in creating engaging images. In short, we recommend exploring and creating first, then circling back to the underlying geometry. This method avoids the pitfall of getting bogged down by theory without seeing its practical applications.

2) Guidance from Production Veterans: The depth and clarity this lesson offers stem from its authors, who bring years of hands-on production experience to the table. One key reason this content sets itself apart is its focus on industry conventions and practical nuances often glossed over by traditional educational resources. These include the intricacies of matrix notation and Cartesian coordinate systems' representation. Having navigated the complexities of computer graphics on professional grounds, our contributors have encountered the challenges of piecing together these fundamental concepts without guided instruction. Their experiences, marked by a journey of self-learning amidst professional demands, motivate this lesson's comprehensive approach. We aim to spare you the confusion and frustration that can accompany learning these critical concepts in isolation. By sharing our insights, borne from extensive experience, we offer you a clearer path through the maze of computer graphics, ensuring you benefit from hard-earned knowledge that only production veterans can provide.

3) Acquiring Essential Skills: By the end of this lesson, you'll have grasped the majority of the tools and concepts essential for rendering, shading, and computer graphics programming. This includes a thorough understanding of vectors, points, normals, matrices, and how to manipulate these elements using trigonometric functions. While some advanced topics like matrix determinants, quaternions, and rotation methods around arbitrary axes are reserved for dedicated lessons due to their complexity, you'll still emerge with about 80% of the geometric knowledge crucial for CG programming. Future lessons will delve into matrix determinants and quaternions, further broadening your understanding.

By completing this lesson, you'll achieve a significant milestone in your journey into computer graphics, equipping you with a solid foundation to tackle more complex topics and projects.

Fundamentals of Geometry

In the realm of computer graphics, understanding points, vectors, matrices, and normals is as fundamental as the alphabet is to writing. Consequently, most textbooks on computer graphics start with discussions on linear algebra and geometry. However, delving into complex mathematical concepts at the outset can be daunting for those eager to learn about image creation. If the thought of engaging with mathematics or the concept of a matrix makes you hesitant about pursuing computer graphics programming, don't be discouraged just yet.

We kick off the "Foundation of 3D Rendering" segment with lessons that don't presuppose a background in linear algebra, deliberately opting for a less traditional method of teaching CG programming skills. This approach allows you to engage with practical, enjoyable activities early on, such as creating a basic ray tracer that demands minimal mathematical and some programming knowledge. Embarking on renderer construction offers a dynamic and gratifying way to learn mathematics, providing immediate visual feedback on the application of various concepts (e.g., your resulting image). Nevertheless, it's imperative to understand that points, vectors, and matrices play a crucial role in generating computer graphics images, and we'll be relying on them heavily throughout our lessons.

This lesson aims to demystify these elements, elucidate their functionality, and introduce methods for their manipulation. It will also shed light on the diverse linear algebra conventions adopted by CG researchers over time for problem-solving and coding. Familiarity with these conventions is essential, as they are often overlooked in literature and online resources. Before engaging with another developer's code or methodologies, verifying their conventions is crucial.

A brief aside for those with a strong inclination toward mathematics: you might find the inclusion of concepts not strictly tied to linear algebra unusual. Our objective is to broaden the lesson's scope to encompass basic mathematical techniques frequently employed in computer graphics, even if they only tangentially relate to vectors and matrices. For example, from a strict mathematical standpoint, points are not a part of linear algebra (which focuses solely on vectors). Yet, we choose to explore points due to their prevalence in computer graphics, applying similar mathematical strategies for their manipulation. If you're still unclear about the differences between points and vectors, don't fret—we'll delve into that in detail throughout this chapter.

What is Linear Algebra? Introduction to Vectors

Linear algebra is a crucial field of mathematics focused on the study and manipulation of vectors. You might wonder, "What exactly is a vector, and why is it significant in computer graphics (CG)?" Simply put, a vector can be thought of as an array or sequence of numbers, varying in length, which mathematicians often refer to as a tuple. When specifying the size of a vector, we use the term "n-tuple," where "n" signifies the vector's element count. For instance, a vector with six elements would be represented in mathematical terms as:

$$V = (a, b, c, d, e, f),$$where each of a, b, c, d, e, f represents real numbers (such as 1, 3, 4.56, -11, -13.08, 0, and so forth).

The purpose of organizing these numbers into a vector is to convey a specific value or concept that holds significance within the problem's context. In the realm of CG, vectors play a pivotal role as they can denote positions or directions within a space. Moreover, vectors are subject to transformations—a set of powerful and succinct operations that alter their values. These transformations, known as linear transformations, are fundamental tools in CG for modifying vector attributes. While we will delve deeper into transformations in future discussions, it's essential to understand their critical role in the application and theory of linear algebra within computer graphics.

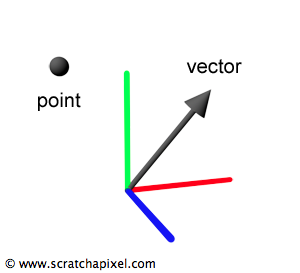

Points and Vectors

In the realm of computer graphics, the concepts of points and vectors play a fundamental role, each serving a distinct purpose within a three-dimensional space.

A point is essentially a specific location in a three-dimensional space. It marks a precise position without indicating any direction or magnitude. This is akin to pinpointing a spot on a map, where the main interest lies in the spot's location rather than in the direction or distance from another spot.

Conversely, a vector represents both a direction and a magnitude (or size) within the same three-dimensional space. Vectors can be visualized as arrows that point from one location to another, indicating the direction of travel from the starting point (origin) to the end point, along with the distance between these two points. The representation of three-dimensional points and vectors employs the tuple notation introduced earlier:

$$V = (x, y, z),$$where \(x\), \(y\), and \(z\) are real numbers that define the vector's direction and magnitude in space.

It's important to note that the interpretation of vectors and points can vary significantly across different scientific fields. Mathematicians and physicists, for example, often adopt a more generalized view of these concepts, where a vector can encompass an arbitrary or even infinite number of elements, far beyond the three-dimensional scope commonly used in computer graphics.

Toward the end of this chapter, we touch upon the concept of homogeneous points. For certain mathematical operations, such as matrix multiplication, it becomes convenient to introduce a fourth element to the point notation, resulting in homogeneous coordinates:

$$P_H=(x, y, z, w).$$Homogeneous points facilitate certain transformations and operations within computer graphics. While they might seem complex at first glance, their utility will become clearer as we progress through the lesson. They're mentioned here to prepare you for their appearance in the literature and to avoid any confusion, with a promise of a more in-depth discussion to follow.

A Quick Introduction to Transformations

Let's delve into how linear transformations, such as translation and rotation, apply to points and vectors in computer graphics (CG), simplifying their manipulation within three-dimensional space.

Translation is a fundamental operation that involves moving points to different locations in space. When we talk about translating a point, we refer to shifting its position from one place to another without altering its orientation or size. This operation is akin to picking up an object and placing it elsewhere. However, translation doesn't apply to vectors in the same way because a vector's essence lies in its direction and magnitude, not its starting position. Thus, moving a vector without changing its direction or length means it remains the same vector, regardless of where it's positioned in space.

For vectors, rotation is a more relevant transformation. Rotating a vector changes its direction while keeping its starting point and magnitude constant. This operation is like spinning an arrow around a point in space: the arrow points in a new direction, but its length and starting point remain unchanged.

Here's a simple representation of these concepts:

-

Point transformation: \(P \rightarrow \text{Translate} \rightarrow P_T\)

-

Vector transformation: \(V \rightarrow \text{Rotate} \rightarrow V_T\)

The subscript \(T\) denotes the "transformed" version of the original point or vector.

One aspect we haven't explored yet is the significance of a vector's magnitude or length in CG. The length of a vector is critical because it determines how far in a given direction it extends. A vector is considered normalized when its length is exactly 1, maintaining its direction but scaling its magnitude to a unit length. Normalization is a common requirement in CG for simplifying calculations and ensuring consistency across different operations. Yet, there are scenarios where maintaining the original length of a vector is beneficial, such as when the vector represents a specific distance between two points (e.g., from point \(A\) to point \(B\)), providing both direction and the measure of separation between them.

Normalizing vectors can sometimes be a tricky process, leading to errors if not handled correctly. Thus, it's essential to always be mindful of whether a vector should be normalized based on its intended use. Each time you work with a vector, questioning its normalization status can help avoid common pitfalls, ensuring your CG operations yield the desired outcomes.

Normals

In computer graphics and geometry, the concept of a normal is crucial for defining the orientation of a surface at a specific point. A surface normal at a point \(P\) on a surface is essentially a vector that is perpendicular to the tangent plane at that point. This means it points directly away from the surface, indicating its orientation in three-dimensional space.

Normals are indispensable in the process of shading, a technique used to determine the brightness and color of surfaces in a scene based on the light sources present. By understanding the orientation of a surface through its normals, computer graphics algorithms can accurately simulate the effects of lighting on different parts of an object, contributing to the realism and depth of the rendered scene.

It's important to note that normals, while similar to vectors in that they have both direction and magnitude, are treated differently in terms of transformations. This distinction arises because the way normals interact with light and shadow depends on their orientation relative to light sources, not just their position in space. As a result, transforming normals requires special consideration to maintain the correct lighting effects on the surface of an object after it has been moved or altered in the scene.

Further exploration of how normals are transformed will be covered in the dedicated chapter on transforming normals. For now, understanding the basic concept of normals as vectors perpendicular to surfaces, and their role in shading, lays the foundation for more advanced topics in computer graphics related to lighting and rendering.

From Theory to C++

In your C++ code, employing a single Vec3 class to represent points, vectors, and normals offers a streamlined approach to handling these distinct but related geometric entities. This unified representation aligns with practices in well-regarded libraries like OpenEXR, optimizing for efficiency and code conciseness. The choice to use a single class over separate classes for points, vectors, and normals is a design decision that balances the benefits of reduced code complexity against the potential for semantic errors.

template<typename T>

class Vec3

{

public:

// 3 most basic ways of initializing a vector

Vec3() : x(T(0)), y(T(0)), z(T(0)) {}

Vec3(const T &xx) : x(xx), y(xx), z(xx) {}

Vec3(T xx, T yy, T zz) : x(xx), y(yy), z(zz) {}

T x, y, z;

};

typedef Vec3<float> Vec3f;

Vec3<float> a;

Vec3f b;

The Vec3 template class you've described allows for versatile instantiation with different data types (e.g., float, int, double), making it adaptable to various precision requirements in graphics applications. The class is structured to initialize a three-dimensional entity with either default values of 0 or specified values for each axis, providing flexibility for different use cases.

Here's a brief breakdown of the class structure and its implications:

-

Template Parameter

Vec3withfloat,int,double, etc., depending on the precision needs of your application. -

Constructors: The class includes three constructors for versatile initialization:

-

Default constructor initializes all components to 0, useful for creating a zero vector.

-

Single-value constructor initializes all components to the same value, convenient for creating vectors with uniform values in all directions.

-

Three-value constructor allows for explicit specification of each component, offering the most flexibility.

-

-

Public Members

x,y,z: Direct access to the components of the vector (or point, or normal) simplifies the manipulation and readability of the code but requires careful handling to maintain clear distinctions between how these entities are used in different contexts.

While using a single Vec3 class for points, vectors, and normals can simplify the codebase, it necessitates a disciplined approach to using the class. Specifically, when applying transformations, it's crucial to remember the semantic differences between points (locations in space), vectors (directions and magnitudes), and normals (perpendicular orientations to surfaces) to ensure correct calculations. For example, transformations like translations affect points but not vectors or normals in the same way, whereas rotations might affect vectors and normals but not points.

Adopting this approach means that some operations, particularly transformations, may require specific handling or additional functions to correctly interpret the Vec3 instance's role in a given context. This design decision emphasizes the importance of clear documentation and possibly helper functions or methods that abstract away the complexities of correctly transforming these entities based on their intended interpretation.

Summary

This initial chapter provides a foundational understanding of key concepts in computer graphics (CG), emphasizing the mathematical and practical aspects of vectors, points, and their transformations within a three-dimensional space. Here's a concise summary of the critical points covered:

-

Vectors in CG are defined as entities that convey direction within a three-dimensional space, represented by three numerical values. This definition narrows down from the broader mathematical perspective of vectors, which can exist in any dimension.

-

Points are understood as specific locations in 3D space, also represented by three numbers. This distinction between points and vectors is fundamental in CG, as it influences how each is used in modeling and transformations.

-

Homogeneous points are an extension of the concept of points, represented with four numbers instead of three. They are a specialized case that facilitates certain mathematical operations, such as transformations involving perspective projections, which will be explored in more detail later.

-

The concept of linear transformations is introduced as a means of modifying points and vectors. These transformations can include operations like translation (for points) and rotation (for vectors). The principle behind linear transformations is that they preserve the linear and geometric properties of the entities they modify, such as lines and planes.

-

Normalization of vectors is highlighted as a process of adjusting a vector's length to 1 while maintaining its direction. The original length of a vector can be crucial in certain algorithms, as it represents the distance between two points.

The chapter also hints at the importance of understanding how points and vectors are situated within a coordinate system—a framework that allows for the precise definition and manipulation of points and vectors in space. The coordinate system, serving as a reference or origin, is crucial for interpreting the three numbers that define points and vectors in both two-dimensional and three-dimensional contexts.

What's Next?

As we progress, the next chapter will delve into the intricacies of coordinate systems, providing a deeper understanding of how points and vectors are contextualized within space. This discussion will lay the groundwork for more advanced topics in computer graphics, including transformations, modeling, and rendering, by establishing a clear framework for spatial reference.