Ray-Triangle Intersection: Geometric Solution

Reading time: 16 mins.Ray-triangle Intersection: Geometric Solution

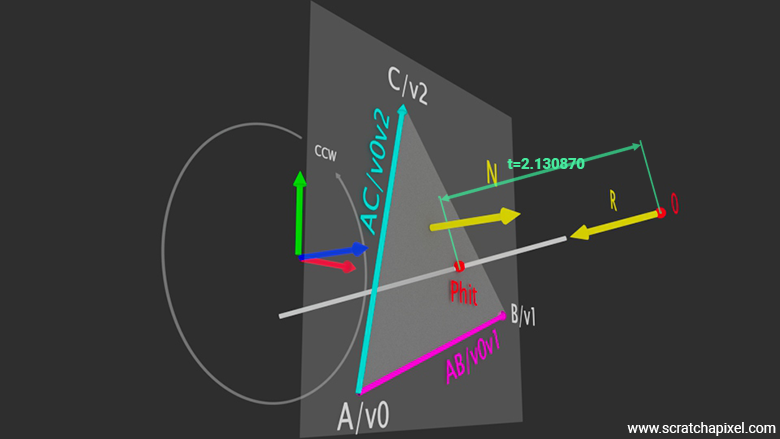

In the previous paragraphs, we learned how to calculate a plane's normal. Next, we need to determine the position of point \(P\) (in some illustrations, we also used "Phit"), the point where the ray intersects the plane.

Step 1: Finding P

We know that \(P\) is somewhere on the ray defined by its origin \(O\) and its direction \(R\). We used \(D\) in the previous lesson, but we will use \(R\) in this lesson to avoid confusion with the term \(D\) from the plane equation. The parametric equation of the ray is (equation 1):

$$P = O + tR$$Where \(t\) is the distance from the ray origin \(O\) to \(P\). To find \(P\), we must find \(t\) (refer to Figure 1). What else do we know? We have already computed the plane's normal and the plane equation (2), which is (refer to the chapter on ray-plane intersection from the previous lesson for more details):

$$ \begin{array}{l} Ax + By + Cz + D = 0 \\ D = -(Ax + By + Cz) \end{array} $$Where \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\) are the components (or coordinates) of the normal to the plane (\({N}_{\text{plane}} = (A, B, C)\)), and \(D\) is the distance from the origin \((0, 0, 0)\) to the plane. If this is still unclear, imagine a sheet of paper passing through the origin, which you rotate around the origin. Once you are satisfied with the plane’s orientation, move it some distance away from the origin in the direction perpendicular to your sheet of paper. The variables \(x\), \(y\), and \(z\) represent the coordinates of any point on this plane.

Knowing the plane's normal and that the triangle's vertices \(v_0\), \(v_1\), and \(v_2\) lie in the plane, it is possible to compute \(D\). Let's choose \(v_0\) for this purpose (you can choose \(v_1\) or \(v_2\) as well):

float D = -dotProduct(N, v0); // Or, if you want to compute the dot product directly: float D = -(N.x * v0.x + N.y * v0.y + N.z * v0.z);

We also know that point \(P\), the intersection point of the ray and the plane, lies within the plane. Consequently, we can substitute \({P}\) (equation 2) for \(O + tR\) in equation 1 and solve for \(t\) (equation 3):

$$ \begin{array}{l} A(O_x + tR_x) + B(O_y + tR_y) + C(O_z + tR_z) + D = 0 \\ t = -\dfrac{(A \cdot O_x + B \cdot O_y + C \cdot O_z + D)}{(A \cdot R_x + B \cdot R_y + C \cdot R_z)} \\ t = -\dfrac{{N} \cdot {O} + D}{{N} \cdot {R}} \end{array} $$float t = -(dot(N, orig) + D) / dot(N, dir);

With \(t\) computed, we can now calculate the position of \(P\):

Vec3f Phit = orig + t * dir;

Wow! Cool, that was kind of easy, but remember that this only gives us the point where the ray intersects the plane in which the triangle lies. The intersection point itself could still be outside the triangle's boundary. So, we are not done yet. We still need to test whether the intersection point \(P\) is inside the triangle (or lies on one of the triangle's edges or vertices). But before we get to that, there are two important cases we need to consider first.

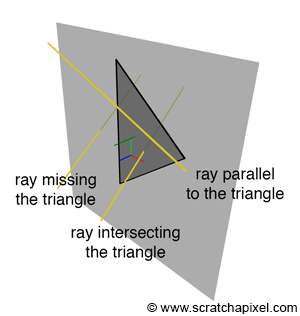

The Ray And The Triangle Are Parallel

If the ray and the plane are parallel, they will not intersect (refer to Figure 2). For robustness, we must handle this case should it occur. This situation is straightforward to identify: if the triangle and the ray are parallel, then the triangle's normal and the ray's direction are perpendicular.

We know that the dot product of two perpendicular vectors is 0. Referring to the denominator of equation 3 (the term below the line), we compute the dot product between the triangle's normal \(N\) and the ray direction \(R\). Our code must be robust to prevent a potential division by 0. When this term equals 0, the ray is parallel to the triangle, indicating no intersection. Hence, before calculating \(t\), we first evaluate \(N \cdot R\); if the result is 0, the function will return false, indicating no intersection.

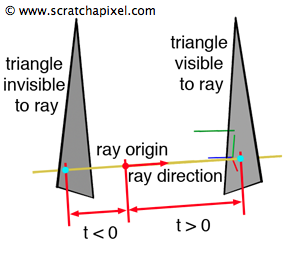

The Triangle is "Behind" the Ray

Until now, we have assumed the triangle is always in front of the ray hitting the triangle. But what if the ray is located "behind" the triangle (having passed the triangle) while maintaining its direction? By the way, don’t confuse this with the case where the ray hits the triangle from the back. So, we have two cases here:

-

Case 1: The ray can hit the triangle from either the front or the back. In this case, the ray is either in front of or behind the triangle, but the ray's direction is always aiming at the target.

-

Case 2: The second case is like an archer standing either in front of or behind the target but always shooting the arrow forward. In the virtual world, an archer standing behind the target and shooting an arrow forward could still hit the target. How cool is that?

We’re concerned about case 2 here. When the archer is behind the target, shooting the arrow forward, the arrow typically shouldn't hit the target—it should land somewhere in front of the archer and be lost forever. Similarly, in our case, the triangle should not be visible if the ray originates behind it and is traveling away from it. However, Equation 3 can still yield a valid result in this scenario. Fortunately, this situation is easy to detect: when the ray starts behind the triangle, the value of \(t\) is negative, meaning the hit point lies in the opposite direction of the ray’s travel (the hit point would be "behind" the archer). Failing to account for this could mistakenly include the triangle in the final image, which is undesirable.

Again, don’t confuse this with the case where the ray hits the triangle from the back—that’s a perfectly valid scenario, like seeing someone whether you’re looking at them from the front or the back. But if you’ve turned your back to someone, you wouldn’t expect to see them, right?

Conclusion: We must check the sign of \(t\) before confirming the intersection as valid. If \(t\) is less than 0, the triangle is behind the ray's origin relative to its direction, meaning it is not visible (the "turned your back" scenario), and we should return false for no intersection. On the other hand, if \(t\) is greater than 0 (you're looking at the person, whether it's their face or back), the triangle is "visible" to the ray, and we can proceed to the next step.

Step 2: Is \(P\) Inside or Outside the Triangle?

Now that we have identified the point \(P\), where the ray intersects the triangle's plane, we need to determine whether \(P\) is inside the triangle (indicating that the ray intersects the triangle) or outside it (indicating that the ray misses the triangle). Figure 2 illustrates these possibilities.

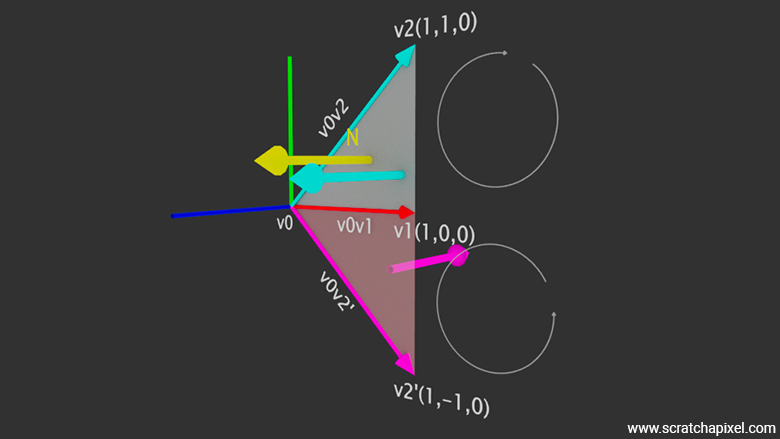

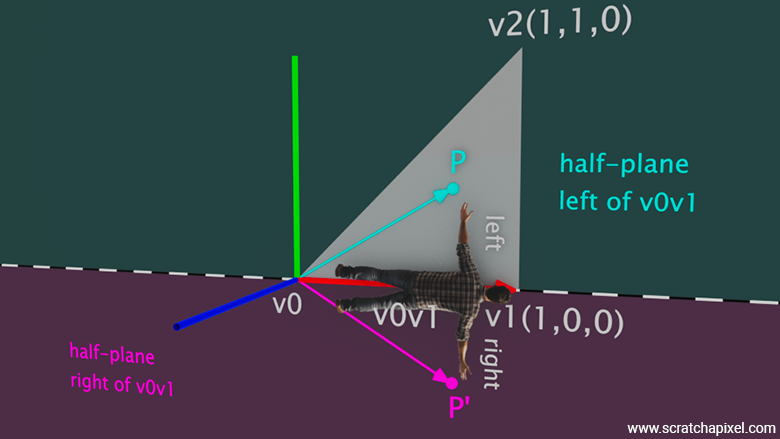

The solution to this problem is straightforward and is called the inside-outside test. We have already encountered this term in the lesson on rasterization, where the test was applied to 2D triangles. Here, we adapt it for 3D triangles. Let's define the vectors \(v0v1\) and \(v0v2\) as shown in Figure 4. Calculating the cross product of these two vectors yields a result that points in the same direction as the z-axis and the triangle's normal (we could also use \(v0v1\) and \(v1v2\) or \(v0v1\) and \(v2v0\) for calculating the normal, but that's a detail).

$$ \begin{array}{l} v0v1 = (1, 0, 0) \\ v0v2 = (1, 1, 0) \\ {v0v1 \times v0v2}_x = v0v1_y \cdot v0v2_z - v0v1_z \cdot v0v2_y = 0 \\ {v0v1 \times v0v2}_y = v0v1_z \cdot v0v2_x - v0v1_x \cdot v0v2_z = 0 \\ {v0v1 \times v0v2}_z = v0v1_x \cdot v0v2_y - v0v1_y \cdot v0v2_x = 1 \cdot 1 - 0 \cdot 1 = 1 \\ {v0v1 \times v0v2} = (0, 0, 1) \end{array} $$Now, let's mirror \(v2\) across the x-axis, calling this mirrored point \(v2'\), with coordinates \((1, -1, 0)\). The cross-product \(v0v1 \times v0v2'\) would result in \(v0v1 \times v0v2' = (0, 0, -1)\).

$$ \begin{array}{l} v0v1 = (1, 0, 0) \\ v0v2' = (1, -1, 0) \\ {v0v1 \times v0v2'}_x = v0v1_y \cdot v0v2'_z - v0v1_z \cdot v0v2'_y = 0 \\ {v0v1 \times v0v2'}_y = v0v1_z \cdot v0v2'_x - v0v1_x \cdot v0v2'_z = 0 \\ {v0v1 \times v0v2'}_z = v0v1_x \cdot v0v2'_y - v0v1_y \cdot v0v2'_x = 1 \cdot (-1) - 0 = -1 \\ {v0v1 \times v0v2'} = (0, 0, -1) \end{array} $$-

Since \(v0v1 \times v0v2\) and \(N\) point in the same direction, their dot product is positive.

-

Conversely, since \(v0v1 \times v0v2'\) and \(N\) point in opposite directions, their dot product is negative.

You may have noticed that when we follow the vertices in the order \({v0} \rightarrow {v1} \rightarrow {v2'}\), we rotate clockwise, whereas in the order \({v0} \rightarrow {v1} \rightarrow {v2}\), we rotate counterclockwise. As you might recall from the lesson on geometry, the normal direction is defined by this vertex order. If the normal \(N\) is calculated by going around the triangle vertices in one particular order, you will get \(-N\) if you calculate the normal by going around in the opposite direction. Keep this in mind.

This test reveals that if a point \(P\), which lies in the plane of the triangle (such as vertex \(v2\) or the intersection point), is on the left side of vector \(v0v1\), then the dot product between the triangle's normal and the cross product \(v0v1 \times v0v2\) is positive.

The key point here is understanding the role of the point \(P\) in this method. In our previous example, we used \(v2\) to calculate the vector \(v0v2\). However, let's now imagine that \(P\) represents some arbitrary point in the plane, not necessarily vertex \(v2\). The logic remains the same. We calculate the vector \(v0P\), and if the dot product between the triangle's normal and \(v0v1 \times v0P\) is positive, we know that \(P\) is on the left side of the vector \(v0v1\).

Conversely, if the dot product between the triangle's normal and \(v0v1 \times v0P\) is negative (as in the case where we use a point \(P'\), like the mirrored vertex \(v2'\)), then \(P\) is on the right side of \(v0v1\).

These two cases are illustrated in Figure 5. If point \(P\) is inside the triangle, then the dot product between the triangle's normal and the vector \(v0v1 \times v0P\) will be positive, indicating that \(P\) is on the left side of the imaginary line defined by \(v0v1\), which effectively divides the triangle's plane. If point \(P'\) is outside the triangle, specifically in the half-plane to the right of the line defined by extending the vector \(v0v1\), then the dot product between the normal of the triangle and the vector obtained from calculating the cross product between the vector \(v0v1\) and \(v0P'\) will be negative.

To apply the technique described for the ray-triangle intersection problem, we perform the left/right test for each triangle edge. If point \(P\) is on the left side of each of the triangle's edges, where each edge is calculated as \(e_{n} = v_{(n+1) \% 3} - v_{n}\), then \(P\) is inside the triangle (where \(n\) is the vertex index, and for triangles, this number varies from 0 to 2). If the test fails for any edge, \(P\) lies outside the triangle's boundaries. Figure 6 illustrates this process.

Another way of looking at it is to consider that each edge of the triangle, \(e_{n} = v_{(n+1) \% 3} - v_{n}\), cuts the plane on which the triangle lies into two: what's on the left of that edge and what's on its right. "Left" and "right" are defined with respect to the direction of the vector \(e_{n} = v_{(n+1) \% 3} - v_{n}\). To determine whether \(P\) is on the left or right of that edge, follow these steps:

-

Calculate the vector from \(v_n\) to \(P\): \(v_nP = P - v_n\).

-

Calculate the vector \(e_{n} = v_{(n+1) \% 3} - v_{n}\).

-

Compute the cross product between these two vectors. Let's call it \(N_p\).

-

Calculate the dot product between \(N\), the triangle's normal, and \(N_p\). The sign of this dot product tells us whether \(P\) is to the left or right of that edge \(e_n\).

-

Repeat this for every edge of the triangle (this method also works for polygons with more than three edges, as long as the polygon is convex).

Here is an example of the inside-outside test in pseudocode:

Vec3f v0v1 = v1 - v0;

Vec3f v1v2 = v2 - v1;

Vec3f v0v2 = v0 - v2;

Vec3f v0p = P - v0;

Vec3f v1p = P - v1;

Vec3f v2p = P - v2;

if (dotProduct(N, crossProduct(v0v1, v0p)) > 0 &&

dotProduct(N, crossProduct(v1v2, v1p)) > 0 &&

dotProduct(N, crossProduct(v0v2, v2p)) > 0) return true; // P is inside the triangle

Note the similarities between this method and the method used in the rasterization lesson to determine if a pixel overlaps a (2D) triangle.

Let's write the complete ray-triangle intersection test routine code. First, we'll compute the triangle's normal, then test if the ray and the triangle are parallel. If they are parallel, the intersection test fails. If not, we compute \(t\), from which we can determine the intersection point \(P\). If the inside-out test is successful (testing if \(P\) is on the left side of each of the triangle's edges), then the ray intersects the triangle, and \(P\) is within the triangle's boundaries, making the test successful.

bool rayTriangleIntersect(

const Vec3f &orig, const Vec3f &dir,

const Vec3f &v0, const Vec3f &v1, const Vec3f &v2,

float &t)

{

// Compute the plane's normal

Vec3f v0v1 = v1 - v0;

Vec3f v0v2 = v2 - v0;

// No need to normalize

Vec3f N = v0v1.crossProduct(v0v2); // N

// Step 1: Finding P

// Check if the ray and plane are parallel

float NdotRayDirection = N.dotProduct(dir);

if (fabs(NdotRayDirection) < kEpsilon) // Almost 0

return false; // They are parallel, so they don't intersect!

// Compute d parameter using equation 2

float d = -N.dotProduct(v0);

// Compute t (equation 3)

t = -(N.dotProduct(orig) + d) / NdotRayDirection;

// Check if the triangle is behind the ray

if (t < 0) return false; // The triangle is behind

// Compute the intersection point using equation 1

Vec3f P = orig + t * dir;

// Step 2: Inside-Outside Test

Vec3f Ne; // Vector perpendicular to triangle's plane

// Test sidedness of P w.r.t. edge v0v1

Vec3f v0p = P - v0;

Ne = v0v1.crossProduct(v0p);

if (N.dotProduct(Ne) < 0) return false; // P is on the right side

// Test sidedness of P w.r.t. edge v2v1

Vec3f v2v1 = v2 - v1;

Vec3f v1p = P - v1;

Ne = v2v1.crossProduct(v1p);

if (N.dotProduct(Ne) < 0) return false; // P is on the right side

// Test sidedness of P w.r.t. edge v2v0

Vec3f v2v0 = v0 - v2;

Vec3f v2p = P - v2;

Ne = v2v0.crossProduct(v2p);

if (N.dotProduct(Ne) < 0) return false; // P is on the right side

return true; // The ray hits the triangle

}

This "inside-outside" technique works for any convex polygon. Repeat the method used for triangles for each edge of the polygon. Compute the cross-product of the vector defined by the two edges' vertices and the vector defined by the first edge's vertex and the point. Then, compute the dot product of the resulting vector and the polygon's normal. The sign of the resulting dot product determines if the point is on the right or left side of that edge. Iterate through each edge of the polygon. There's no need to test the other edges if one fails the test.

Note, this technique can be optimized if the triangle's normal and the value \(D\) from the plane equation are precomputed and stored for each triangle in the scene.

What's Next?

In this chapter, we introduced a technique for computing the ray-triangle intersection test using simple geometry. However, there's more to the ray-triangle intersection test that we haven't covered yet, such as determining whether the ray hits the triangle from the front or the back. We can also compute the barycentric coordinates of the intersection point. These coordinates are essential for tasks such as applying a texture to the triangle.