Single vs Double Sided Triangle and Backface Culling

Reading time: 6 mins.Single vs. Double-Sided Triangle

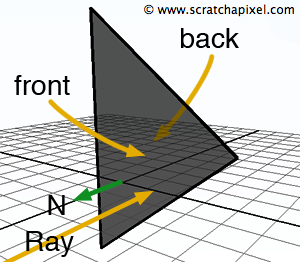

We've previously discussed the term back-face culling in the lesson on rasterization, but let's revisit it. Imagine developing a routine to compute the intersection of a ray with a triangle. We create a scene using a right-hand coordinate system, where the triangle's vertices are defined in a counter-clockwise order. The triangle is positioned five units away from the ray's origin, which is located at the world coordinate system's center \((0, 0, 0)\). The ray is oriented along the negative z-axis. We know how to compute the triangle's normal, which, by construction, aligns with the positive z-axis if all of the triangle's vertices lie in the x-y plane or a plane parallel to it. Remember that the orientation of the normal depends on the coordinate system's handedness and the order in which the triangle's vertices are defined (also known as winding). As shown in Figure 1, the ray direction and the triangle's normal face each other.

The surface of a primitive with its normal pointing outward is defined as the outside surface, while the opposite side is known as the inside surface. Changing the handedness of the coordinate system or the order of the vertices will flip the normal's direction, effectively swapping the inside and outside surfaces. This surface orientation affects surface visibility and shading. While shading is not our current focus, let's consider the issue of visibility.

In a CG scene, primitives with their outside surfaces facing the camera are considered front-facing. Conversely, when the outside surface of a primitive faces away from the camera, it is considered back-facing. Rendering programs often allow the discarding of any primitive that is back-facing during the visibility stage of the rendering process, making only the primitives whose outside surfaces face the camera (front-facing) visible. For example, OpenGL provides such controls. These primitives are referred to as single-sided (visible only when their outside surface faces the viewer). To render a primitive visible regardless of whether its surface is facing towards or away from the camera, you can declare the primitive as double-sided. Some rendering programs do not offer the option to designate primitives as either single or double-sided; instead, they either systematically discard all back-facing primitives (making them invisible in the final frame) or default to making them all double-sided. The RenderMan specifications allow you to specify on a per-primitive basis whether an object should be treated as single or double-sided (using the RiSide call). Additionally, RenderMan specifications provide options to define the scene's coordinate system handedness (with the RiOrientation procedure) and to reverse the orientation of a primitive's surface in relation to the coordinate system's handedness (if desired) with the RiReverseOrientation call.

Real-time APIs such as Vulkan, Metal, or DirectX also provide the capability to control whether the vertices that define triangles are specified in a counter-clockwise or clockwise order and whether back-facing triangles should be discarded. This configuration is typically done while defining the graphics pipeline in the primitive/assembly state.

// Using Vulkan API rasterization_state.polygonMode = VK_POLYGON_MODE_FILL; rasterization_state.cullMode = VK_CULL_MODE_BACK_BIT ; rasterization_state.frontFace = VK_FRONT_FACE_COUNTER_CLOCKWISE;

The term back-face culling (or simply "removal," if you prefer) means that objects whose normals point away from the view direction will not be drawn on the screen. Enabling back-face culling ensures that polygons, triangles, surfaces, etc., whose normals do not face the view direction, won't be rendered. Only geometry with normals facing the camera will be visible in the final image.

This technique can significantly increase rendering speed and reduce memory usage in z-buffer-style renderers by potentially decreasing the number of surfaces rendered by a substantial margin. For example, theoretically, 50% of the faces of a polygonal sphere could be culled.

With ray tracing, this feature is not as advantageous because, generally, we want all scene geometry to cast shadows, regardless of the object surface's orientation relative to the ray direction. However, back-face culling is still useful for primary rays. If a polygon's surface normal deviates by more than 90 degrees from the viewing vector (as illustrated), it could be excluded from intersection tests. A simple dot product test between the normal and the view direction is sufficient to determine whether the face should be culled.

Naturally, we do not cull the face if the object is declared double-sided. Additionally, culling back-facing surfaces may not be desirable for transparent objects.

The image above illustrates the faces (in orange) that will be culled at render time if the object is opaque, rendered as a single-sided object, and back-face culling is enabled.

Putting It Together

When developing a rendering program, it is crucial to ensure that it accommodates all potential scenarios. Providing users with the ability to select the coordinate system handedness, reverse surface orientation if necessary, and define whether primitives are single or double-sided can significantly affect what is visible in a frame, even for the same geometry.

For instance, the choice of coordinate system handedness affects the direction of the normal, which is defined by the triangle's vertices \(v_0, v_1, v_2\). In a right-hand coordinate system, the normal (computed from the triangle's vertices) points towards you (away from the screen, assuming the x-axis is pointing to the right). In this scenario, the ray-triangle intersection routine will return false if back-face culling is enabled, even if the ray intersects the triangle. Conversely, switching to a left-hand coordinate system will reverse the normal's orientation (the normal will point away from you, in the direction of your line of sight), making the intersection test successful. In the first scenario, the triangle would not be visible, while in the second, it would be—even though it is the same triangle.

Here is an implementation for the single/double-sided feature. At the start of the function, compute the dot product of the triangle's normal with the ray direction. If the dot product is negative, the vectors point in opposite directions, indicating that the surface is front-facing. If the dot product is positive, the vectors point in the same direction, meaning that we are looking at the inside (or back) of the surface, making it back-facing. If the primitive is declared single-sided, it should not be visible in this case, and the function should return false.

bool intersectTriangle(point v0, ..., const bool &isSingleSided)

{

Vec3f v0v1 = v1 - v0;

Vec3f v0v2 = v2 - v0;

Vec3f N = crossProduct(v0v1, v0v2);

normalize(N);

...

// Implementing the single/double-sided feature

if (dotProduct(dir, N) > 0 && isSingleSided)

return false; // The surface is back-facing

...

return true;

}